THE DALTON

Stories that Alistair wrote whilst he was out on his adventure

THE DALTON

Stories that Alistair wrote whilst he was out on his adventure

THE DALTON

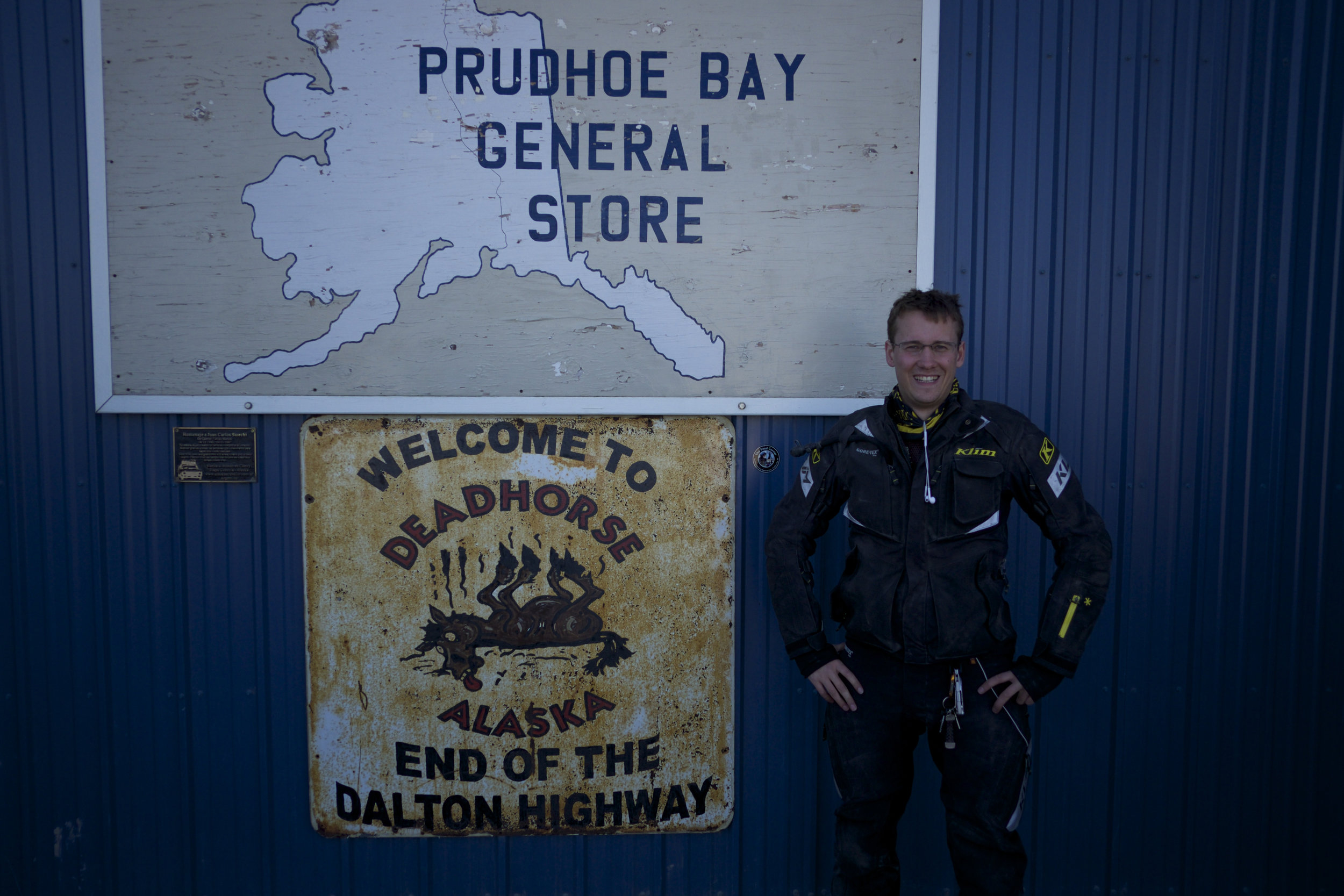

The following is a story that Alistair wrote whilst travelling along the Dalton highway in Alaska, USA

THE DALTON: PART 1

“Whirr, click”

“Have you tried putting into neutral?” asked Jim, a KLR rider from Canada that I had met the nightbefore.

THE DALTON: PART 2

“If you think about it, you’ll hesitate and bitch out….”

It’s early morning, on the 4th of July weekend and instead of swilling beer and singing patriotic songs, I was standing in nothing but small blue briefs, surrounded by fog, at the edge of the Arctic Ocean.

The Dalton: Part 1

The Dalton: Part 1

The Dalton: Part 1

“Whirr, click”

“Have you tried putting into neutral?” asked Jim, a KLR rider from Canada that I had met the nightbefore.

“Whirr, click”

The Kawasaki 650 motorbike that I had bought a week ago, with under a 1000 miles on the clock had broken down on the Dalton highway. Possibly one of the remotest stretches of road in the world, the Dalton is a 414-mile stretch of road that was built in 1974 to support the oil fields in Prudhoe Bay and was only opened to the public in 1981. Where I have broken down is at least 120 miles from the nearest tow truck and over 300 miles from the nearest motorcycle mechanic.

Naturally, this remote and untamed stretch of road (I maintain that a highway is too generous of a term) is a Motorcyclists’ Mecca.

Oh, and if you do break down, it costs at least 5 bucks a mile to be towed. With my budget of $50 a day, breaking down isn’t really an option.

Getting a tow truck is enough of a challenge, there is no phone reception for the entire road until you get to Prudhoe Bay or civilisation back in Fairbanks. The only real option is to be saved by one of the 160 or so truckers that barrel along the road every day in summer (there are about 250 in winter).

“Whirr, click,”

I looked over to Jim, who smiled ruefully into the clear Alaskan sky “It’s what happens on the road, you’re going to have to get used to it over the coming year” he said.

I am 2 weeks into my year long trip from Alaska to South America, I’ve got 24 years to my name and 3 years riding experience (on a humble Honda Cbr250 I might add). I had set off from Anchorage a few days earlier to head north through Alaska, pass the arctic circle and go for a quick dip in the Arctic before heading south on my 28,000 or so mile journey to the southern tip of South America.

Jim and I begin to pull apart my bike, unscrewing what had been until earlier that day, pristine black fairings. In good weather, a chemical called calcium chloride is sprayed along dirt sections of the road. This chemical dries quickly in the sun, and reduces the dust while compacting the loose layer of rich brown soil above the permafrost and makes the road a lot more manageable.

However, when this delightful little bastard mixes with water it becomes a sticky muck that sets harder than concrete once dry and can cause all sorts of mischief to bikes and trucks alike.

Pulling my bike apart, I think about the various decisions that had led to this point, knees covered in mud as I slide the fairings off and Jim offers helpful advice over my shoulder.

Early that week, I had been chatting to Christina in Anchorage, a guide at Motoquest (who run adventure motorcycle tours throughout the Alaskan wilderness and the rest of the world). “The truckers are Gods up there, we have had truckers take pity on a rider and drive them for nothing to Anchorage… we have also heard of riders that were run off the road”

Naturally, as a trucker barrels passed at about 80 miles an hour, both Jim and I (who has been given similar advice) turn to raise a hand and smile.

Generally, most motorcyclists break the Haul road into a 4 stage trip.

1. Fairbanks to Coldfoot- 254 Miles

2. Coldfoot to Prudhoe Bay- 241 Miles

3. Prudehoe Bay to Wiseman ( a small off-road outside of Coldfoot) -233 Miles

4. Wiseman to Fairbanks- 241 Miles

I had camped the night previously with Jim and John, 2 Canadians who were travelling through Alaska on KLR’s. I had already been on the road a week and welcomed the company and chance to learn more about the KLR from them.

Sitting in the muck as I furiously turned a 8mm wrench, about to take the seat off, I was thanking God silently for Jim’s steadying presence on the other side of the bike. Also the fact that our mutual love of a beer after a hard days’ riding had led to us talking about bikes and now travelling him and his buddy. Travelling alone leads to incredible experiences, but can be trying when experiencing slight “technical difficulties”.

The mornings’ ride had been nothing short of spectacular, we were just coming down from the Antigun pass where we had had stopped for lunch and my bike and run into some trouble.

Above: Antigun Pass rises 4,739 Feet and cuts through the the Brooks Range.

Now, with the seat precariously balanced on top of my left pannier, Jim and I peered at the battery and various electrical additions I had made to my bike. Heated Grips, GPS charger and a trickle charger (allowing me to charge my iPhone) all seemed to be ok until I peered a little closer to the positive side of the battery.

“ Try tightening the screw..?” muttered Jim, as I handed him a screwdriver from my tool kit.

Jim began to screw the little bolt in as I tried to figure out which animal Jim would like to have sacrificed in his honour if it worked. Perhaps a sheep? We had past Caribou on the way up but that seemed like too easy a gesture. Only a sheep or perhaps a

pure white bull…. “Yep, loose as hell” exclaimed Jim, jolting me out of my reverie.

Jim looked up at me and nodded.

I turned the key, gunned the throttle and my bike sprang to life.

“She works!” laughed Jim, leaning back and smiling with quiet victory written all over his face. I had also promised him a beer if we figured it out.

As I begin to pickup my tools and re-assemble the bike, I look over to Jim who was pulling his jacket back on and asked a question that had never occurred to me before. “Jim, why “she”?

He laughed and turned to look at me.

“Something as dangerous as this could only be female”

It’s going to be an interesting year.

The Dalton: Part 2

The Dalton: Part 2

The Dalton: Part 2

“If you think about it, you’ll hesitate and bitch out….”

It’s early morning, on the 4th of July weekend and instead of swilling beer and singing patriotic songs, I was standing in nothing but small blue briefs, surrounded by fog, at the edge of the Arctic Ocean.

“….so don’t think about it, just jump”

Brandon's, (the tour guide for the mornings’ trip the arctic ocean) words of wisdom had seemed so simple sitting in the warmth of the tour bus an hour earlier. Standing almost butt naked on the edge of near freezing deep blue water, I again questioned my sanity.

Technically, you can’t go swimming in the near freezing water near Prudhoe Bay. I and a few others did happen to “fall in” though. The fact that we were dressed in our swimming gear is besidesthe point. An Argentinean man, tanned, sinewy and about 50 years old strides casually into the near freezing water, armed with goggles and a swimming cap. He smiled ruefully at the cold before breaking into a lazy backstroke. Determined to not to be out done by a baby-boomer with an amazing moustache, I girded my loins and made a run for it.

As I plunged into the water, all sorts of expletives crossed my mind. Some of them around the fact that I was wearing just underwear (my swimmers were conveniently at the bottom of one of my panniers back in Prudhoe bay) and that there were more than just a few women watching. Once fully submerged though, I couldhave almost sworn that the Titanic soundtrack could be heard in the distance and I finallyappreciated why Rose refused to share her life raft with Jack.

As I stepped (ran) out of the water and tried to stride (again, ran) confidently back towards the small group of people who had left the warmth of the small bus, I started to mumble the typical male excuses around “It’s rather cold…” Laughter sparkles in Amandas' eyes as she throws a towel at me and shares a laugh with her mum.

I had met Amanda and her family the day previously at Coldfoot camp and played leapfrog with them the entire way up to Prudhoe Bay. The family of 5 make the pilgrimage every year up the Dalton highway to observe the more than 170 different species of birds that live along the Trans-Alaskan Pipeline.

I start to feel warm in the cold arctic air and think perhaps that I am blushing, then realised that its impossible to blush to your toes, particularly considering that I could no longer feel my feet. I hurried to throw my clothes back on and get back to the warmth of the bus.

As I furiously began to rub various parts of my body, (eliciting somewhat inappropriate and disapproving looks from a nearby family of 3) Brandon continued his rolling discussion of the Trans-Alaskasn pipeline, the very reason I was able to fall into the frigid of arctic water so conveniently.

“The pipeline is about 800 miles long and cost about 77 billion dollars to make….. in 1977”

As we drive slowly back to the Prudhoe bay hotel, it again struck me just how desolate this place is, despite it being run by a staff of several thousand in peak times who work mainly in shifts of 2-3 weeks on then with a similar amount of time off. There are some roles, particularly those that involve oil, that the “on time” can run into the months. Apparently the time off (and the money that goes with it ) is worth it.

“It’s not a bad place, just rough on families, the lack of beer isn't the best thing in the world either” comments a worker who asked not to be named. Since oil was found in 1968, there has been a constant stream of people and infrastructure pouring into this tiny area some 250 miles north of the Arctic circle. The pipeline itself pumps some 45,000 to 50,000 barrels of oil each and every day, inhuge steel pipes that were specially made in Japan with such precision that even the welds are X-rayed before each piece is put into use, let alone the stringent requirements a replacement part